Debra Damo

|

|

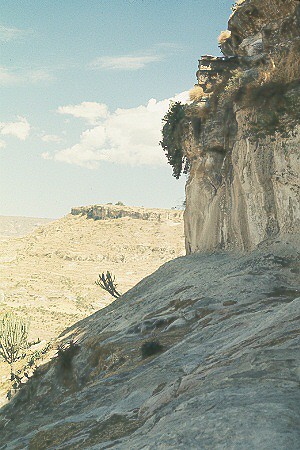

For the last 10 miles (16 km) we had seen Debra Damo off and on between the other mountains. It looked like an huge oblong box sitting ungainly on the top of a high mountain with steep sloping sides. The vertical walls of the amba (mesa in the U.S. west) looked to be 100 feet (30 meters) or more high.

We were in the middle of the second day of a three-day trip, Mickey on his 500cc BSA Victor and I on my 250 Ducati. We had already spent a day in Axum. Now we were traveling east on the Adi Abun-Adigrat road as we approached a small bridge near the 43 km (27 mile) marker. It hadn't rained for six months and the day was middle-of-the-desert dusty, hot, and dry.

To the left of the bridge, a dirt road led off north to the Ethiopian Coptic monastery of Debra Damo on top of the mountain. A sign with a cross on it identified the road, but any message had long since rusted away. I guess, one time it must have said something like, "Monastery this way" or "Debra Damo."

We bumped off the main road onto a rutty, rock-strewn track. The first 5 miles (8 km) though rough were over comfortably rolling country. No great challenges, just a few ruts and rocks. After we passed through a small village, things changed. The rutted trail descended steeply into a valley 150 feet (46 meters) below.

At the bottom of the valley, a shallow ford crossed a creek with a moderate amount of water. With the dry season in full swing, I was surprised to see any water at all. In Asmara, we were trucking water 28 miles (45 km). With this much water in the dry season, in the rainy season, we probably could not have crossed this ford, even with a four-wheel-drive vehicle.

We studied the creek bed and the opposite bank for a while before committing ourselves. The opposite bank was a steep, 20-foot (6-meter) climb through rocks and gravel. I suppose someone had decided the rocks would give larger vehicles more traction. They gave us more headaches.

After picking our paths, I lead the way, gaining as much momentum as safety would allow before entering the water. I bounced around on the slippery rocks. When I finally emerged on the other side, I was going too slowly. I revved the engine, slipped the clutch, and used both feet to half walk, half ride my way to the top.

Then I stopped while Mickey repeated my maneuver. His cycle was larger so he struggled more than I had. But more than that, the recklessness required by the maneuver was not one of Micky's strong traits.

From the creek we had a long, rough climb along a road surely designed only for carts. The grade on the switchback turns was often almost at the 30 to 40 degree angle of the mountain side. No builder seems to have even tried to flatten them out. I had to use first gear often and even let my wheel spin to keep the engine running fast enough so it had the power to pull me, half walking, around the steep corners.

Mickey said later, "I don't think I would have continued if you were not ahead of me. I might not have even crossed the creek. But I wasn't about to be left behind."

After climbing several hundred feet, we got off the bikes and walked 100 feet (30 meters) up to a rope, the last 60 vertical feet (18 meters) up to the monastery. We walked up well-worn, tan, sandy rock, the same rock that turned into a vertical wall. This shaded north wall area was 15 to 20 degrees cooler than the scorching air very close by.

|

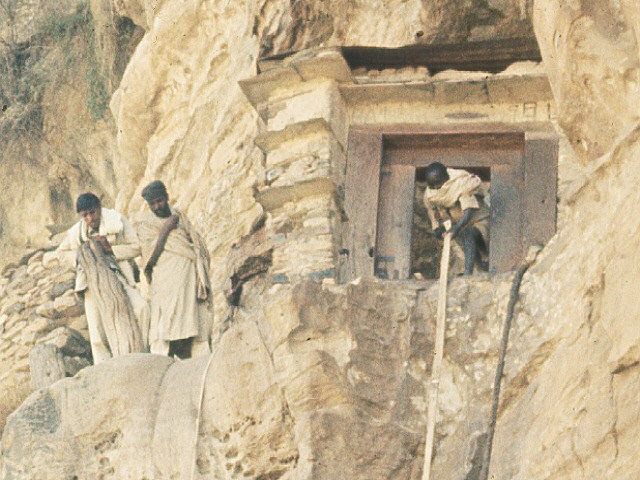

To the left, a house clung to the top of the cliff. Just in front, a leather rope hung down from a four-by-five foot (1.2-by-1.5 meter) opening 60 feet (18 meters) above. A bald man in a shama the color of the cliff's rock stood looking down.

The figure invited us up. "Welcome to Debra Damo. Please, come."

We were in an all-male area. A sign down by the creek said, "No females of any species allowed beyond this point." A similar sign appears near every Ethiopian Coptic monastery. If a female were to be so rash to come this far, the rope simply would not be lowered for her.

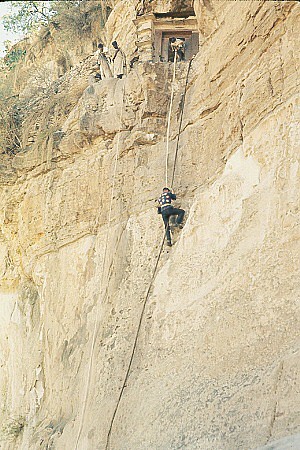

Mickey led. He wrapped a second rope, a safety rope, around his waist, grabbed the first, and began to step into notches in the cliff wall. Step by step he made his way up the wall. The guy in the door kept the safety rope tight around Mickey's waist and finally helped him into the opening.

|

Micky climbs Debra Damo... |

|

Once Mickey was up, I stood frozen at the bottom. My fear of heights determined that I was not going to climb these last few feet, even after the wild trip up the road just below! The gate man on top kept trying to get me to come up. "You come now." "I hold you." "It is easy." "Do not be afraid."

Yes, he had helped Mickey with a second rope. But such a little man up there and such a big man down here to be safely guided to the top. I knew what my fears were in those days. And leaning out over 60 feet (18 meters) of nothing to stick my toe into a notch in the side of a cliff was one of my more dominating fears.

A five-year-old boy scampered up and down no less than five times to show me how easy it was. "Come, Mister." "Come, Mister, it's easy." He said as he grasped the holes in the cliff and glided to the top (without either rope!).

"I know. I know."

During the next ten minutes, 4 or 5 men went up the wall like spiders climbing their webs. They just grabbed the rope, stuck their toes in the holes, and went up as if climbing a set of stairs. Obviously, an everyday activity for them.

Finally, I got up the courage. Curiosity overcame fear. I shouted up to the gate keeper, "Throw down the other rope."

"You come now? Good."

Down came a frayed, old, flat rope. Flop. It didn't increase my confidence much. I tied it around my waist and yelled up, "OK, I'm coming now."

There was no "OK" about it. I was scared as hell. My heart was a lump in my throat as I made the first few steps. Don't look down, Don't look down. I said over and over as I went from notch to notch to notch in the wall, moving up another foot with each step. I felt like a caterpillar clinging tightly to the wall.

Each step became a little easier than the last. Soon I was grappling into the four-by-five foot (1.2-by-1.5 meter) opening, the gateway to the monastery. The old, grinning monk, pulled me the last few inches over the edge as he repeated, "Welcome to Debra Damo."

"Thank you." I sighed deeply, trying to dispel the thought of going down the same way.

"Go here." The gate keeper said pointing up stairs cut into the rock.

I found Mickey nearby. We walked past hanging vegetation and several stone buildings. Soon we were on top. It was flat, just as flat as it looked from afar.

We walked 50 yards (45 meters) to the edge. What a view! Mountains everywhere. And deep valleys. "Don't get so close to the edge, Mickey, please. My heart can't take it."

A young monk dressed in a clean, tan shama approached and in broken English said, "Welcome to Debra Damo. I am Brother Tesfai."

"Thank you, Brother Tesfai. I am Mike. This is Mickey. We have come to see your monastery and Enda Abuna Aragawy church."

"You are very welcome. Abuna Aragawy is our founder. When he arrived below Debra Damo, no one was living here. No one was here before. Only a large snake lived here. God commanded the snake to help Abuna Aragawy. The snake let his tail down and helped the abuna to the top of Debra Damo. Then Abuna Aragawy made this great monastery of Debra Damo."

Other historical evidence points to the King Gebra Maskal, the son of King Kaleb, as the one who established this monophysite monastery around 525 CE.

"Now you come to see this holy church. Come this way." He led us between several small stone buildings.

"How many monks are here at Debra Damo?" Micky asked.

"Maybe, there are 300 monks, counting the novices." He was as precise as all polite Ethiopians are. They never give you an exact number. It's always, "Maybe...." But that "maybe..." was usually pretty close.

"Where do you get your food? I see only those small fields." I asked pointing to a couple plots of feeble-looking wheat that could not have been enough for 25.

"We grow our food in fields below Debra Damo. You went past fields when you come here." Indeed, we had. That meant most of their food came up the steep road, not to mention the rope.

"Here is Enda Abuna Aragawy. Please, come inside."

We had come around a building into a small open area in front of beautiful church. It looked as if it were straight out of ancient Axum. The wall was formed of alternate layers of wood and rock. Along the top of each layer of wood, what looked like the top of poles stuck out every foot or so. These protrusions are called monkey heads. The building's windows looked like the carved windows in the stelae at Axum. Wooden beams formed the four sides of the window; square monkey heads accented each corner.

|

(Picture by Skip (Bruce) Dahlgren) |

We entered through a two-door entrance formed by three square columns. Just after the first entrance was another into a small area. Little squares covered the ceiling of this second room, each contained different detailed carvings of cows, horses, ibexes, lions, vegetation, and patterns.

Once fully inside, we stood in the back of an intimate little building. It smelled dusty dry with a faint hint of incense. I don't remember much about the interior beyond my feeling of awe. I was standing inside a building built so long ago, a building so steeped in Ethiopian history.

The church Enda Abuna Aragawy is often considered the oldest Christian church in Ethiopia. It likely was built before the ninth century. Influenced heavily by Axumite architectural elements, it is one of the best examples of early Christian churches in Ethiopia.

"We have no wells. God gives us in the rain. We store water in these holes." He took us to a couple large, cubical cisterns carved out of the rock. They were partially filled. A bright green mass floated on the water. A stench I cannot describe filled the air. "You want drink?"

"No, thanks."

Many stone buildings, all with corrugated iron roofs, were scattered close to each other on the north end of the amba. Some surely had no more than one room. Others must have had many. "Do all the monks live in these buildings?"

"All monks and novices live on Debra Damo. But some very holy monks also live in caves along the side of Debra Damo."

"You mean on the wall of the mountain? How do they get there? Are there paths to the caves?" Micky asked.

"No paths. Another monk must let them down on rope. There is no other way. They are very holy men."

"How big are the caves?"

"Some are like big room in a house. Others are so small holy man maybe cannot stand up. Holy man especially like little places because they can be alone with God."

"How does a monk in a cave get food to eat?" I interrupt.

"One time each day another monk lets food down to him on rope so he can eat."

"What if the monk wants to get out of the cave?"

"He can come out any time. He just asks and another monk brings him up on rope. But holy men stay in the caves long time to get close to God."

We were now walking back toward the gate and its roap. My stomach and insides began to tighten.

We gave Brother Tesfai gifts of paper, pencils, and matches for the monks.

"Thank you very much for gifts and thank you for visiting our holy monastery of Debra Damo. Please, come again."

Brother Tesfai walked us to the gateway and the rope. I took one look and panicked. Why had I come up? Mickey tied the safety rope around his waist, reached down and grabbed the other rope, and slipped out of sight over the edge. The gate keeper kept enough tension on the rope to catch him in case he missed a step. Soon he was down.

My turn now. My heart was in my throat. No choice this time. When the end of the security rope was back up, I tied it around my waist. What really bothered me was that the main holding rope was attached to the bottom and off to the side of the gate. While leaning out and over to grab it, I also grabbed a look down. Wa! to put it as a true Ethiopian. Wa! the universal Ethiopian explanation point--of joy, sorrow, excitement, fear, ... and panic.

As the gate keeper gently reassured me, I got a knuckle-whitening grip on the rope and squeegeed around groping with my feet for a place in the wall to put them. Ah, a place for my right toe. Then one for my left. Stop thinking about where you are and don't look down. I did and didn't. Soon I was on the bottom glad I had gone up, and very glad I was down. I let out a very deep breath.

The cycle ride down the mountain was little more than an easy afterthought after the cliff. Though easier than going up, parts of the ride were probably a lot more dangerous. The gravel was loose and we had to brake a lot. It's much easier to get out of control and slip or fall off a mountain when going down, especially steeply down.

|

Before long, we were back at the creek, then across on the other side. As I looked back up at Debra Damo, I recalled that it had also been a prison for Ethiopian royal family members in the 9th and 10th centuries and then again in the 14th through 16th centuries. A few brothers and sisters held on a mountaintop cannot ferment rebellion elsewhere in the kingdom.

Thank you for your interest in this page. This is a full function preview page for this book. If you have come to this page from outside the www.WorksAndWords.com web site, perhaps you are not aware that this is one chapter in Ethiopia: Travels of a Youth, a CD-ROM book available here for $13.95. |